This month, News and Reviews for the Youth Librarian presents a rare discussion between two renowned children’s authors.

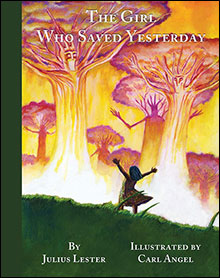

Marissa Moss, the award-winning creator of the Amelia series, interviews master storyteller and multiple award winner Julius Lester (Newbery Honor, National Book Award finalist, and others) about his life, career, and his latest children’s book, The Girl Who Saved Yesterday.

You have combined an amazing career as an academic scholar and an award-winning children's book writer. How do you balance these very different interests?

I’ve always been interested in a lot of things - music, art, literature. I was in my early teens when my mother said to me, “You’re spreading yourself too thin. You should pick one thing and stick with it.” I responded, “God wouldn’t have given me all these talents if He hadn’t meant for me to use them.” Mother didn’t broach the subject again.

Over the course of my life I was a photographer during the civil rights movement; a folksinger who recorded two albums for Vanguard records; I had a talk radio show in New York City for 7 years, co-hosted a television in New York for two years, taught for 32 years at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in the Afro-American Studies, History, English, and Judaic Studies departments, and published close to 50 books of non-fiction and fiction for children, young adults, and adults.

Someone reading this might wonder how I did such different things. To me they didn’t feel different. Whatever I was doing, I was attempting to communicate the essence of an experience. I enjoyed the challenge of learning how to communicate using different tools - writing, photography, teaching.

Your first book was a guitar-playing guide, co-authored with Pete Seeger. How did you go from that to children's books?

My very first book was How to Play the Twelve-String Guitar as Played by Leadbelly which I co-authored with Pete Seeger. My next book was Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get our Mama! It was the very first book on the Black Power movement of the late 1960s. My editor on that book thought that I had a writing style that would be good for children’s books. She asked me if I’d like to meet the children’s book editor. Fortunately, I said, yes. I’d never thought about writing for children, but the children’s book editor, Phyllis Fogelman, and I talked, and we hit it off. She asked if I had any ideas for children’s books. I’d been doing research on my own for more than 2 years on the experience of slavery in the words of those who’d been slaves. I hadn’t thought about what I’d do with my research, but sitting in her office I told her that I wanted to do a book on what it was like to have been a slave.

She was interested and asked me to write her a short description. I did so. She liked it. The book was To Be A Slave, and it was chosen as a Newbery Honor Book in 1969. Thus, my career in children’s books was born.

You've also written adult novels. How is that process different from when you write for kids?

Writing is hard work regardless of age group. Writing for children is a little harder, perhaps, because children read more closely. Just as writers pay attention to every word, so do children. But it’s all very hard work.

You have won many awards, among them the Newbery Honor, Boston-Globe Horn Book Award, Coretta Scott King Award, National Book Award finalist, ALA Notable Book, National Jewish Book Award finalist, National Book Critics Circle Honor Book and the New York Times Outstanding Book Award. Is there an award left you're still waiting for?

All the ones I haven’t received starting with the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Tell us about the book The Girl Who Saved Yesterday. How did it get started?

That’s hard to answer. I have no recollection of when I wrote the first draft or what led to the writing of that draft. But the story has its inception in a personal need to reconcile with death. I grew up in a slum neighborhood in Kansas City, Kansas in the 1940s. By the time I was 9, three children I’d known had been killed, one of whom was a girl I used to walk to school with whose robe caught fire as she walked by the pot-bellied stove in the kitchen. She was getting ready for school, and she burned to death. My father was a minister, and funerals of church members were not uncommon. And, every Sunday morning when my father said the blessing, he would say, “One of us might not be here next Sunday.” Imagine hearing that every Sunday when you’re a kid.

Who I am has been shaped by death. The same is true for other children. I wanted to write a book for children like me who are exposed to the mystery of death at a very early age, and wonder. This story feels timeless, like a folktale. Why did you choose that kind of format?

Death is timeless. Writing about death requires a format reflective of that.

Your use of language is wonderfully rich, with beautiful metaphors throughout. Do you think this kind of poetic density is difficult for young readers or especially apt?

I am as concerned about the music of language as I am the words making sense. Because language is still fresh for young readers, the way I use language in this book will confirm them in the new ways they look at things and express themselves. Because language is fresh to young readers, my language here will not be difficult to follow but will confirm them in their sense of the possibilities inherent in language if one cares about words.

Death and remembering the dead is a difficult subject, but you've handled it with beauty and grace, leaving the reader with a sense of love and memory rather than one of sadness and loss. What inspired you to approach death this way? Do you know someone like Yesterday, someone who taught you how to honor the dead and keep them alive through memories?

Part of this I answered above.

I suppose I learned to honor the dead through my father who liked to talk about the past and the dead. I’ve learned a lot about honoring the dead through being Jewish. Jewish practice asks us to light a candle each year on the anniversary of a loved one’s death and let it burn for 24 hours. Doing so is like bring the deceased’s spirit back into the world for that period of time, and I find it quite comforting.

The dead have taught me to honor them. I’ve had experiences with the dead through which I’ve learned that they are present and want to be remembered.

What do you want readers to take away from this book? Who do you write your books for?

Oh, dear. I never know how to answer the second question. I don’t write with a particular audience in mind. I’m a storyteller. I tell stories for whomever will listen.

What do I want readers to take away from the book? One day you will be someone’s ancestor. And trees talk. They really do. I have no idea what readers should take from the book. Readers bring themselves to the act of reading just as I brought my self to the act of writing. Bottom line - I hope readers close the book feeling, “I really enjoyed that.” And then wondering about life which is just as big of a mystery as death.

Lastly, do you have a favorite “library moment” you’d like to share with our readers?

I was 13 when we moved to Nashville, Tennessee, in 1952. The libraries were segregated, and the "colored" library was some distance on the other side of town, while the main library was downtown and much closer to where I lived. Even though I could not check books out of the main library since it was reserved for whites, I went there anyway looking for Alexander Thayer's 3 volume biography of Beethoven. As I walked in I was terrified, as I could have been arrested. I walked up to the main desk where three women stood. Two women looked at me and turned away. The third woman was much younger. She looked at me and seemed as scared as I'm sure I looked, but instead of turning away, she walked up to me.

"May I help you?" she asked, her voice trembling.

I told her what I was looking for, in an equally quavering voice.

She told me to follow her, and she took me into the stacks to the very volumes I was seeking. I don't recall that we exchanged any words after those at the desk. Having the books in my hands, and I really did want to read them, I decided I would press my luck and try to check them out. The same young woman had to know that she was breaking the law, but she took my card, put a date stamp in the books, and I walked out of the library with them.

The next time I went to the library, she was not there, and I never saw her again. Whether that had anything to do with her helping me, I don't know. But more than 60 years have passed, and I have not forgotten that she chose to join me in defying southern history and law. In such small acts, history is made.

|